Posts nobody asked for

- not-so-hidden-now: true

- tags: google, cloud, pipelines

Hundreds and Hundreds

There's the original post but it's possible to make edits here.

We maintain and update more than 800 Google Cloud projects. That number grows every day. And all runs under 10 minutes.

The pipelines are automated and almost completely autonomous. This means that most Pull Requests are automatically approved and merged. Even changes that affect all projects run under 10 minutes.

We'll cover the why we centralised all these projects. Then the how to make it work. Finally how to make it fast.

TL;DR

A combination of centralised yaml files, Python running Terraform and GitHub matricised jobs.

The problem

When you have a single digit number of projects, you start by having

different Terraform root modules for each project, consuming upstream

modules. The differences in those upstream modules are extracted into

terraform variables. Then you cd into those project directories and run

some sort of terraform init + plan + apply command cycle. Easy.

With double digits, it's possible, but tedious to operate the same way. Copy-paste-tweaking Terraform files are how new projects are created. The script that loops over directories and deploys them works just as fine. It would just take a wee bit longer.

With hundreds of projects, it's just not feasible.

I feel the need. The need for structure

(And speed! But definitely structure.)

The conundrum that developers want flexibility and speed but operations want stability is solved by putting flexibility on the dev box and stability on prod. Staging is a mini production that catches errors before it hits the production fans. This often means resources you deploy on dev need to be replicated somehow on the other 2 environments. And since in Google Cloud the best isolation mechanism to reduce the blast radius is the project, this leads to more copy-pasting-tweaking.

In larger organisations, functionality like Single Sign On, private shared networking, connectivity to OnPrem, security, log analysis and incident alerts are managed centrally. And the design that achieves this is the poorly named Landing Zone. It basically defines a structure that all workload projects need to hook up with.

All projects need to connect with several points of the Landing Zone. And you want that from the very start. This sets a minimal set of functionality every project should have baked at creation. This implies managing these projects centrally.

Project drift

There's also the risk of snowflake environments. They happen when upstream modules are updated but the root (project) module lags behind the latest changes. The project hasn't done an apply recently.

This is akin to snowflake servers and creates a drift between the Infrastructure as Code and their live deployments.

The way to fight this is to ensure new changes get rolled out in a consistent way to all.

Bored humans

With a large number of projects, you can imagine how having slow, error-prone, bored humans reviewing and approving Terraform plans, potentially for hundreds of projects, each with potentially a hundred resources or more, becomes a bottleneck. Not even to mention inefficient.

It's impractical to maintain hundreds of projects with manual reviews. The reviews could be done by the developer teams but all projects need those minimal set of features, connected to the central structure. At the very start. Before they are handed out to developer teams.

Centralising these projects under this single vending machine allows covering 90% of the Terraform plan validations. The rest 10% can be flagged for inspection.

Enter yaml

Firstly and foremostly, we extracted all config, not into tfvars files, but into yaml files. Could be JSON or TOML but yaml is human-friendly enough and, as opposed to no-dangling-commas-quote-everything-JSON and weirdly nested TOML, you can add comments.

Better still, Terraform can natively load yaml and using the locals

block you can massage that data before feeding it off to the resources

and their loops.

A bare minimum project in yaml can look like this:

project:

name: Data Analytics POC

prefix: data-analytics-poc

status: active

environment: sandbox

network: standalone

owners:

- tyrell.wellick@ecorp.com

- whiterose@deus.net

labels:

cost-centre: CC-1234

app-type: analytics

Other project settings can include creating service accounts, groups, custom IAM roles, APIs to enable, WIF bindings, etc. This list grows with every sprint.

If you are thinking: "Bruh! You just traded 800 small directories for 800 yaml files". Correct. But now it's 800 centralised files.

Now we can do interesting things.

Enter Python

One of the benefits of using yaml and not say .tf or .tfvars

files is that other languages can more easily process these files.

This enables validating the projects' settings as much as possible.

Validation

Validation is a requirement for automatic approvals and autonomous pipelines.

The yamale python library offers just that. Besides validating against a basic schema, it allows users to hook up custom validators. For example, some check if certain combinations of values are allowed (Google doesn't like the use of some restricted strings, such as google and ssl).

Others see if the owners are valid users or if a role or budget threshold is authorised. The list of auto-approved, manually approved or straight up denied settings also live in yaml files. Which means they can be extended as needed via pull requests.

In short, pulling these definitions into Python adds more flexibility than Terraform could ever offer. One could argue that the Terraform CDK allows this too but running this from Python allows us to control things between an init and a plan and between a plan and an apply.

State fixing

All Terraform commands are called from Python and for us, this turned out to be significant. Because some projects were migrated from a flat hierarchy to the Landing Zone tree structure and some resources had to be imported to avoid duplication and eventual deployment errors. Also, people tend to create some things manually and then add them later to the project settings. So between an init and a plan, we import resources and mend some things.

Note

In practical terms, an initial

terraform plan -refresh-onlycall is made and then imports and fixes are done to the terraform state, paving the way for a clean terraform plan and apply.

Another benefit of having Python wrapping Terraform (see what I did there) is speeding up Terraform calls by parallelising python and therefore Terraform calls at a project level. More details on this below.

Plan safety

Between a terraform plan and a terraform apply we parse the

Terraform plan to ensure only some resources are allowed to be

destroyed. One can't simply rely on a Terraform plan to error to catch

mistakes, for example because of a typo in the database instance name.

But by parsing the plan we catch and halt that destruction and

recreation. And this is definitely cleaner than sprinkling lifecycle

rules everywhere. These planned deletions checks can be turned off

in a separate and manual pipeline.

Warning

If you are more interested in this, which is a good idea in an auto-approved Terraform world, you can get a json version of the terraform plan with

terraform show -json <plan-file>and then inspect theresource_changesblock.

GitHub's approval

Whereas Python handles the validation and wraps Terraform, GitHub Actions is the glue and plays a critical role in reducing project updates from hours to a maximum of 10 minutes.

The gist

The basic units of GitHub Actions are: workflow, job and step.

Each workflow lives in a yaml file. A workflow run is triggered by certain events, like pushing a commit to a branch or a pull request. Inside a workflow, jobs run in their own separate containers and, by default, run in parallel. Steps inside those jobs are sequential. Typical steps include checking out the code, running a shell script or use plugins, that GitHub calls Actions.

Playing with the API

Apart from a wealth of neat features, GitHub exposes its API to the workflow itself. This means you can write javascript in there and in that inline code you can do API things, like approve and merge PRs. This amount of flexibility and automation in the pipelines means we can enable them to start making decisions.

GitHub exposes its APIs by making 3 objects available: github,

context and core. github is a client to the GitHub API. The others

refer to the event's context and core is used to control the

workflow run itself, and can be used to issue warnings that show in

the run, set environmental variables and more.

A "thorough" example of an approval script:

steps:

- name: Approves pull request

uses: actions/github-script@v6

if: needs.validation.outputs.pass == 'true'

with:

script: |

const payload = {

owner: context.repo.owner,

repo: context.repo.repo,

pull_number: context.issue.number,

event: "APPROVE",

body: "Yolo!",

}

await github.rest.pulls.createReview(payload);

core.info("This is just here to use the core object.");

Note that the if conditional ensures this step is only run if

the value of the pass output for a job called validation is true.

Anything else and it's skipped.

Note

Eventually the PR review code was moved into custom actions, so very little Javascript code is left embedded in the workflow itself. Just because you can write long shell or js scripts inside yaml it doesn't mean you should.

Joining pipes

In GitHub Actions, the outputs of a step or a job can be made

available for subsequent parts of the workflow, cobbling these pieces

together. Other ways to share data are setting environment variables and

artifact uploading. And

sure enough, we needed them all.

The outcome of scripts that validate project definitions, changes, the Terraform plan parser, resource imports and other fixes are finally gathered and combined into a final Javascript decision script that approves and merges the request or creates a reporting comment otherwise. Kudos to GitHub for all this!

The big long (slow)

After having a mostly autonomous CI/CD pipeline, one of the biggest challenges was the total time the Terraform command cycles took.

An average plan for a project took 1 to 5 minutes and an apply took 2 to 10 minutes. When you run that for 40+ projects sequentially, it brought the whole pipeline to a grand total of 4 hours. Unusable.

But now all hundreds of projects run smoothly under 10 minutes. How?

Git diff

It should be obvious but we only run projects that were changed. So a

git diff --diff-filter=A or --diff-filter=TRM is used to check

which actual files were added or modified. But even after this, it

was obvious sequential runs would stay painfully slow. Especially for

changes that touch all projects.

Note

If your next question is: "git diff... against which commit?" that would be a great question! For apply workflows, we store the last successful commit in a bucket. For PRs, GitHub tracks which commit you would be merging into. You can grab that from the

context.

Threads

Since we already run Terraform commands from Python, the next step was to fan out those with Python threads. The gains from going multithreaded was noticeable: 2 to 8 times faster. Since the most expensive calls Terraform does are over the network, the CPU is free for other threads. But that still left us in the hour-long runs ballpark for a measly 40 projects.

Warning

Important note if you are interested in parallelising Terraform: you should not run several Terraform calls from the same directory because each init will overwrite each other's local files. So instead we copy the original Terraform directory and threaded Terraform calls operate from that new temporary directory instead.

Life in the matrix

Finally, the final piece of puzzle that allowed us to break through the slowness was GitHub Actions' matrix strategy.

You can pass one or more lists of scalars to the matrix and GitHub will run a cartesian product for their values. The matrix strategy operates at job level. This means GitHub will fire up as many parallel jobs to satisfy those combinations.

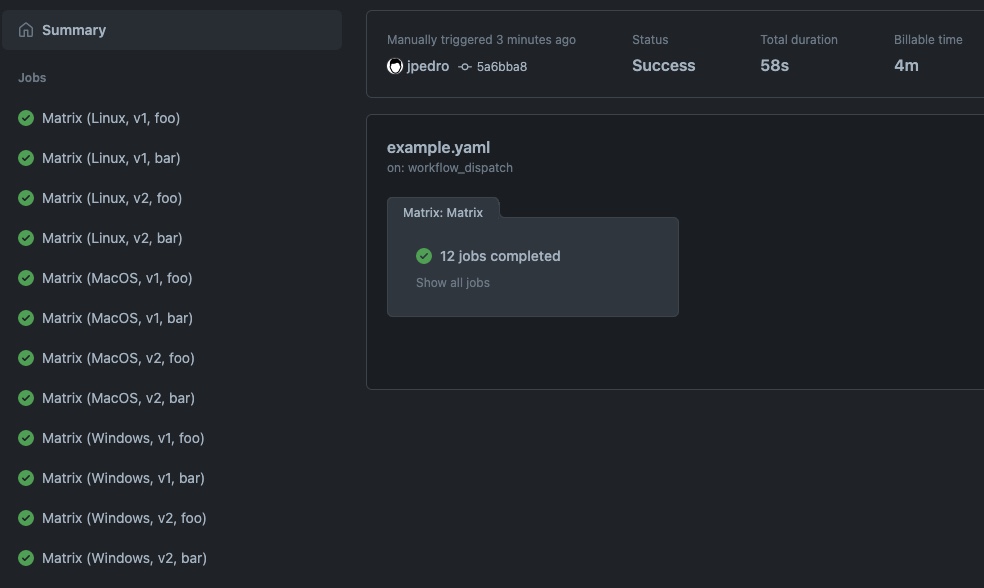

Another "thorough" example:

name: Matrices \o/

on:

workflow_dispatch:

jobs:

matrix:

name: Matrix

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

strategy:

matrix:

os: [Linux, MacOS, Windows]

version: [v1, v2]

component: [foo, bar]

steps:

- name: Build

run: |

echo "Building ${ { matrix.component } } version \

${ { matrix.version } } for ${ { matrix.os } }..."

sleep 30

echo "Done"

That code results in this run:

<!--  --> <!--  -->

Note how GitHub Actions created 12 parallel jobs (3 OSes x 2 versions x 2 components).

Also note how GitHub charges you the minutes across all jobs. That gets

reported under Billable time, which is visible only when different

from the Total duration inside a run. In the screenshot above, it

shows 58s vs 4m.

The fix

The only matrix list we set is a list of slots. Each slot is an

index for a slice of Terraform projects for a job to handle. And that

list is dynamically generated by a script that outputs a list of

changed projects. We set the maximum number of projects per slot at 10.

So if in a commit, 5 projects were changed, GitHub will run 1 job to

handle them. 1234 changed projects means 124 jobs. It's always

Math.ceil(jobs/10).

We use the native GitHub fromJSON function when parsing a valid json

string of values as the matrix list:

slot: ${ { fromJSON(needs.calculate.outputs.slots)) } }

Since these jobs run in parallel and inside each job the Terraform calls are threaded, they all complete in under 10 minutes, no matter the number of projects involved.

Q.E.D. <font color="red" size="1px">■</font>

<!-- $${\color{red}■}$$ -->(Well... not exactly. You will hit some hard limited APIs. Check the Quotas section below.)

Final notes

Now anyone can create a project with a pull request with a yaml file inside, get it approved, merged, provisioned and then get the same sane structure and monitoring that can be extended. Or they can deploy an update to all projects. All done in minutes.

Quotas

Yes – you need to raise those.

If you forget, the fierce Google Cloud APIs limits will remind you. If

you need, you can introduce a delay, via say a time.sleep(slot_index * 5),

to spread each matrix job a few seconds apart. In 80 jobs a delay of 5

seconds means the last job will start 6 minutes after the first job.

That kills the 10 minute bait title of this post but it might be

just enough to survive API limits that can't be further raised.

Landing Zone

Bootstrapping the landing zone itself, managing organizational policies and tags, shared networking, hierarchical firewalls, central monitoring and other LZ functionality is outside of the scope of this article.

They all live happily in their own repos and run in non-threaded, non-parallelised, manually approved, python-unstrangled pipelines.

Because they can.

If you missed it

The title is a reference to Carl Sagan's misquoted expression that was eventually embraced by him into a book.

Made with some <3 not a lot